Of Viking forts, ravaged vessels, and pillaged handcrafts

Perhaps one of my favorite things about Europe is how close and real history is. You can still touch it; be it an old building, an historic ship, or an empty field that was once the battleground of legendary armies. Anywhere you look is an historical site. Perfect!

Perhaps one of my favorite things about Europe is how close and real history is. You can still touch it; be it an old building, an historic ship, or an empty field that was once the battleground of legendary armies. Anywhere you look is an historical site. Perfect! Walking up to the settlement, it looks like little more than a mound in the broad glacial morraine valley that rises slowly from the end of the fjord. Then, as you come over a bank in the valley floor (the former shorline from the Medieval Warm Period when sea levels were higher and glacially compressed land masses were lower) you suddenly notice that you are standing infront of the ruins of a moat and an earthen wall. Recalling scattered bits of Viking history lingering in the back of your mind, you quickly come to feel that you are happening upon sacred ground where legendary events and grave deeds actually took place.

Walking up to the settlement, it looks like little more than a mound in the broad glacial morraine valley that rises slowly from the end of the fjord. Then, as you come over a bank in the valley floor (the former shorline from the Medieval Warm Period when sea levels were higher and glacially compressed land masses were lower) you suddenly notice that you are standing infront of the ruins of a moat and an earthen wall. Recalling scattered bits of Viking history lingering in the back of your mind, you quickly come to feel that you are happening upon sacred ground where legendary events and grave deeds actually took place.

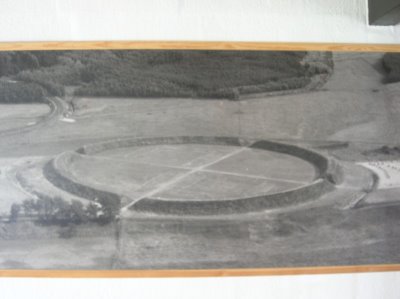

Then, crossing an earthen bridge over the now-dry moat and passing through one of the four symmetrically placed openings in the defensive wall, you enter the fortress site. It appears like a gladiator's arena; broad, flat, and perfectly round. Climbing up the wall it is posible to look out over the amazing site, still clearly evident after 1000 years of erosive rains and farming.

Then, crossing an earthen bridge over the now-dry moat and passing through one of the four symmetrically placed openings in the defensive wall, you enter the fortress site. It appears like a gladiator's arena; broad, flat, and perfectly round. Climbing up the wall it is posible to look out over the amazing site, still clearly evident after 1000 years of erosive rains and farming. At first, the size of the inner court is difficult to appreciate. Being inside, surrounded, and closed in, it just doesn't initially appear all that large. Then as you examine it, walk through it, and gaze up at the high earthen walls, you slowly realize what a mammoth construction this place is.

At first, the size of the inner court is difficult to appreciate. Being inside, surrounded, and closed in, it just doesn't initially appear all that large. Then as you examine it, walk through it, and gaze up at the high earthen walls, you slowly realize what a mammoth construction this place is.

The inside diameter is 120 meters across and the 3 meter wall around it--considerably shorter than it was 1000 years ago before the wooden pickets rotted away and the soil began to wear down--constitutes hundreds of tons of soil that all had to be moved by hand! This fortress is truly an extraordinary construction....there must have been a truly extraordinary threat--and this is over 30 km up a long fjord that would have had watchmen and signal fires dotting its length. Fort Knox is easier to get into than this place!

Perhaps that speaks to the terror of the Viking raiders. The people living here were probably semi-wealthy farmers and merchants. Fyrkat lay along a fine inland trading route that must have been a temptation for the Viking raiding parties--hence the reason for the community to construct the fortress. Inside, archeologists have unearthed the timber ruins of several classic, tapered, Viking longhouses. These were most likely storehouses for these valuable trade goods and living quarters for the defenders during periods of seige.

Perhaps that speaks to the terror of the Viking raiders. The people living here were probably semi-wealthy farmers and merchants. Fyrkat lay along a fine inland trading route that must have been a temptation for the Viking raiding parties--hence the reason for the community to construct the fortress. Inside, archeologists have unearthed the timber ruins of several classic, tapered, Viking longhouses. These were most likely storehouses for these valuable trade goods and living quarters for the defenders during periods of seige. The fortress is now a man-made plateau on a hummock in the valley floor, but in 980 it was an inpregnable island fortress entrenched in the bottom of the fjord. Since then, what is now known as the Medieval Warm Period, when unusually warm temperatures triggered a recession of the icecaps and higher sea levels, has come to an end. Meanwhile, the Northern European landmass has continued to rebound from the crushing pressure of glaciers during the last iceage (Sweden is still rebounding about 10cm every century). The end of the Medieval Warm Period and another 1000 years of landmass rebound has left Fyrkat high and dry.

The fortress is now a man-made plateau on a hummock in the valley floor, but in 980 it was an inpregnable island fortress entrenched in the bottom of the fjord. Since then, what is now known as the Medieval Warm Period, when unusually warm temperatures triggered a recession of the icecaps and higher sea levels, has come to an end. Meanwhile, the Northern European landmass has continued to rebound from the crushing pressure of glaciers during the last iceage (Sweden is still rebounding about 10cm every century). The end of the Medieval Warm Period and another 1000 years of landmass rebound has left Fyrkat high and dry. But in 980 there were wide, shallow channels surrounding the island fortress (one lay where the cluster of trees stands in the depression shown here, a large channel ran along the wall just behind the camera). This water access facilitated the fast Viking-era vessel designs that sailed up the fjord to exchange precious cargoes of grain, wool, and iron implements. These goods were often held in the fortress' storehouses where, secured behind the high walls, they were fairly safe from the fast-moving Viking raiding parties, a group that actually never constituted more than 10% of all Viking peoples. The vast majority of Vikings were simple, peaceful farmers and craftsmen.

Then, having stood in the light breeze absorbing the ambiance of the ancient place, we walked down the bank again. On the way back to the car, you pass through a neat little half-timbered inn, ...

Then, having stood in the light breeze absorbing the ambiance of the ancient place, we walked down the bank again. On the way back to the car, you pass through a neat little half-timbered inn, ... ...under an arched wagon port in a lovely thatch-roofed building...

...under an arched wagon port in a lovely thatch-roofed building... ...and around the corner to where the inn's mill wheel still stands.

...and around the corner to where the inn's mill wheel still stands. This mill house was built beside the Fyrkat site some 700 or 800 years after the Vikings departed, but it too is loaded with history recalling the events of Europe's entry into the industrial revolution. This is what I mean by how you can see and touch history here in all its layers. So much fantastic history just piled up together.

This mill house was built beside the Fyrkat site some 700 or 800 years after the Vikings departed, but it too is loaded with history recalling the events of Europe's entry into the industrial revolution. This is what I mean by how you can see and touch history here in all its layers. So much fantastic history just piled up together. Up the hill from the Fyrkat site on the valley wall, a Viking farming village has been recreated based on the archeological finds at Fyrkat. Ole often works here showing people how the Vikings made rope from the bast layer of linden tree bark.

Up the hill from the Fyrkat site on the valley wall, a Viking farming village has been recreated based on the archeological finds at Fyrkat. Ole often works here showing people how the Vikings made rope from the bast layer of linden tree bark. Like nearly all places in Denmark, there is obviously some strong Danish pride.

The recreated village is a nice little area, an acre or two in size, divided into roughly defined courtyards by a collection of wood and clay structures. Note the arched shape of the roofs, a countour mimmicked in the horizontal plane by the walls, tapering toward the end of the buildings. This is classic Viking design.

The recreated village is a nice little area, an acre or two in size, divided into roughly defined courtyards by a collection of wood and clay structures. Note the arched shape of the roofs, a countour mimmicked in the horizontal plane by the walls, tapering toward the end of the buildings. This is classic Viking design. From the little village, built as accurately as possible given the sketchy evidence from the fortress ruins, one gets a great view out over the valley that was once an extension of the fjord.

From the little village, built as accurately as possible given the sketchy evidence from the fortress ruins, one gets a great view out over the valley that was once an extension of the fjord. Although structural remains have only been found in inside the fortress (the only place archeologists have had the money to really look), it is believed that there were farms like this one climbing the slopes of the fjord for several kilometers in every direction.

Although structural remains have only been found in inside the fortress (the only place archeologists have had the money to really look), it is believed that there were farms like this one climbing the slopes of the fjord for several kilometers in every direction.

Inside, the Viking houses have hard clay floors, high vaulted ceilings to carry the smoke toward the open ends of the building, and a central hearth with iron cooking pots supported on an iron cooking tripod. Examples of this 'camping' equipment have been found on the Oseberg Viking ship, a burial ship unearthed outside Oslo in the 1890s. Bed's were a wooden box on short legs piled with furs.

Fyrkat is certainly a wonderful place where heavy contemplation of the past is unavoidable. It calls to you and seizes your imagination. However, there is one thign that calls to me more; the sea. So, Ole and I climbed in the car and headed down the valley to the little port city lying at the end of the fjord, Hobro.

We waisted no time in satisfying our mutual need for wooden sailing craft. There was a little wooden boatyard right along the town's waterfront. Here, our first nautical find in Hobro, had just emerged from the yard fully restored to a polished and shiny state far finer than this little fishingboat ever enjoyed during its working days.

We waisted no time in satisfying our mutual need for wooden sailing craft. There was a little wooden boatyard right along the town's waterfront. Here, our first nautical find in Hobro, had just emerged from the yard fully restored to a polished and shiny state far finer than this little fishingboat ever enjoyed during its working days.  Across the channel from her stood the last remains of Hobro's commercial trading days, the coal dock where small freighters still come in and offload coal somewhat regularly. Its grubby, industrial appearance--although a landmark for nearly two centuries now--stands out starkly against the rest of the rapidly gentrifying waterfront where shops and cafes are becoming the norm. However, there is one other commercial maritime operation still going on the Hobro waterfront...

Across the channel from her stood the last remains of Hobro's commercial trading days, the coal dock where small freighters still come in and offload coal somewhat regularly. Its grubby, industrial appearance--although a landmark for nearly two centuries now--stands out starkly against the rest of the rapidly gentrifying waterfront where shops and cafes are becoming the norm. However, there is one other commercial maritime operation still going on the Hobro waterfront...

...the Hobro wooden boatyard where historic wooden vessels from all over Denmark come for annual maintenance and even full restoration. Here, Ole walks down to a beautifully restored schooner in for a new coat of hull paint and a battered old fishing boat needing plenty of its rotted timber replaced.

The schooner's lovely prow, her new hull paint glittering in the sun.

The schooner's lovely prow, her new hull paint glittering in the sun. Nearby we found a wooden ketch also in for annual maintenance. Again, the varnish work is more than this vessel has probably ever seen in its life.

Nearby we found a wooden ketch also in for annual maintenance. Again, the varnish work is more than this vessel has probably ever seen in its life. Such beautiful varnish work really must be done indoors so the yeard had a few boathouses, though I can't say how long any of them will last. This one was falling apart as we watched.

Such beautiful varnish work really must be done indoors so the yeard had a few boathouses, though I can't say how long any of them will last. This one was falling apart as we watched.

Interestingly, we learned that no project in wood was too big for the skilled shipwrights in this yard. Inside the shed we found a pathetic wreck of an old fishign smack. Its back was broken (the keel had snapped) and its decks and sheer had flattened out over a sharp bend amidships. It was an absolute wonder that she was even floating--the beautiful flexibility of wood. Even with her structural frame broken in two, the planks held together and kept the water at bay.

Then, rounding one of the boatyard's workshops, we encountered this unique vessel. She was the highlight of the tour for me. Maybe it was her desperate condition or the mystery of the strange fates that had clearly attacked the vessel or maybe I just liked the proportions of her rig. She was a little topsail schooner, her name long worn off her transom.

Then, rounding one of the boatyard's workshops, we encountered this unique vessel. She was the highlight of the tour for me. Maybe it was her desperate condition or the mystery of the strange fates that had clearly attacked the vessel or maybe I just liked the proportions of her rig. She was a little topsail schooner, her name long worn off her transom.  Coming closer, I could see that something horrible had happened to this graceful vessel; Her paint was peeling and seaweed hung in her lubber's net...

Coming closer, I could see that something horrible had happened to this graceful vessel; Her paint was peeling and seaweed hung in her lubber's net... ...some of her planks were sprung....

...some of her planks were sprung....  ...and moss grew in thick layers over the lower shrouds.

...and moss grew in thick layers over the lower shrouds. ...Her metalwork was a mess, the steering gear corroded almost beyond recognition and her chocks torn from their mounts.

...Her metalwork was a mess, the steering gear corroded almost beyond recognition and her chocks torn from their mounts.  Her upper works had been through hell. What happened to this little vessel? How long did she lie on the bottom? How did she get here, floating so well and eagerly tugging at her moorings as if sensing the day's summer warmth and the fine breeze blowin gin from the sea.

Her upper works had been through hell. What happened to this little vessel? How long did she lie on the bottom? How did she get here, floating so well and eagerly tugging at her moorings as if sensing the day's summer warmth and the fine breeze blowin gin from the sea.  Yet she was in no condition to sail with her sprung planks, weakened rigging, and destroyed steering gear. Her entire hull was encrusted with a thick layer of barnacles.

Yet she was in no condition to sail with her sprung planks, weakened rigging, and destroyed steering gear. Her entire hull was encrusted with a thick layer of barnacles.  Yet rather strangely, her rig from the booms on up was in remarkably good shape. Her sails were still bent on and hardly showed any sign of exposure or strife. The poor vessel clearly must have sunk in shallow water.

Yet rather strangely, her rig from the booms on up was in remarkably good shape. Her sails were still bent on and hardly showed any sign of exposure or strife. The poor vessel clearly must have sunk in shallow water.  Perhaps she will be resurrected. Many a vessel lying here in horrid and deplorable condition is only awaiting the skilled and almost miraculous touch of the shipwrights who have shown their power to transform wrecks into seaworthy craft again.

Perhaps she will be resurrected. Many a vessel lying here in horrid and deplorable condition is only awaiting the skilled and almost miraculous touch of the shipwrights who have shown their power to transform wrecks into seaworthy craft again.  Having marveled at the job ahead of these craftsmen, Ole and I wandered the yard a bit more, talked with a maintenance crew aboard this schooner, in very fine shape and just in for a little maintenance and new paint before starting another summer as a youth sailtraining vessel.

Having marveled at the job ahead of these craftsmen, Ole and I wandered the yard a bit more, talked with a maintenance crew aboard this schooner, in very fine shape and just in for a little maintenance and new paint before starting another summer as a youth sailtraining vessel. Then we took a last look around at the old vessels, and headed for the gate.

Then we took a last look around at the old vessels, and headed for the gate.  On the way home to Hornslet, Ole thought we should stop in Randers so I could have a look at the Handworker's museum. Indeed, it was an interesting place to visit, particularly because it has a very unusual organizational structure.

On the way home to Hornslet, Ole thought we should stop in Randers so I could have a look at the Handworker's museum. Indeed, it was an interesting place to visit, particularly because it has a very unusual organizational structure. The whole museum is filled with little stalls exhibiting the workshops of various handworking trades, each exhibiting tools, works in progress, and a few finished example or two. This one is the paint shop. It is cluttered with ladders, paint cans, dropcloths and overalls. It even has huge masses of caked and dried paint from a local painter's shop where the painters repeatedly wiped their brushes. Without doubt this exhibit must be a major fire hazard.

The whole museum is filled with little stalls exhibiting the workshops of various handworking trades, each exhibiting tools, works in progress, and a few finished example or two. This one is the paint shop. It is cluttered with ladders, paint cans, dropcloths and overalls. It even has huge masses of caked and dried paint from a local painter's shop where the painters repeatedly wiped their brushes. Without doubt this exhibit must be a major fire hazard.  Elsewhere in the museum one could find the opticians' shop where glasses are cut and fit into frames, a carpenters' shop, a plaster mouldings maker's shop, a shoemaker etc...etc...

Elsewhere in the museum one could find the opticians' shop where glasses are cut and fit into frames, a carpenters' shop, a plaster mouldings maker's shop, a shoemaker etc...etc...  The amazing thing was that each stall was managed by the local handworkers guild, the members of which donated all the equipment--much of it family heirlooms or objects handed down from master to apprentice a century or more ago. Then these guilds set up the workshop so that the relation between all the tools and materials can be readily seen. The beauty was that no text interpretation was really needed. With handcrafts everyone can figure out the general idea of the trade fairly easily just by taking a lok at the workshop where everything is laid out together.

The amazing thing was that each stall was managed by the local handworkers guild, the members of which donated all the equipment--much of it family heirlooms or objects handed down from master to apprentice a century or more ago. Then these guilds set up the workshop so that the relation between all the tools and materials can be readily seen. The beauty was that no text interpretation was really needed. With handcrafts everyone can figure out the general idea of the trade fairly easily just by taking a lok at the workshop where everything is laid out together.  Moreover, interpretation is also provided via demonstration. Old retirees from each craft guild often come in and do work there, showing people how the shop operated and how they did their work. When we visited, the printer was handing out little signs they had made reading (translated from Danish), "Your mother doesn't work here, CLEAN UP after yourself." That's now hanging in my kitchen.

Moreover, interpretation is also provided via demonstration. Old retirees from each craft guild often come in and do work there, showing people how the shop operated and how they did their work. When we visited, the printer was handing out little signs they had made reading (translated from Danish), "Your mother doesn't work here, CLEAN UP after yourself." That's now hanging in my kitchen.

Of course part of why Ole likes this place so much--aside from the fact he's always been a handworker; first a carpenter and then a ropemaker--is that it has a miniature rope-walk set up in one of the stalls. Sitting among the ropewalk car, the crankhandles, the piles of hemp and linden fibers, Ole often comes in to do demonstrations for visitors.

So, it was certainly an interesting example of an unusal museum structure and adds to my research. Indeed, everything Ole and I visited that day offered interesting insights into preserving our heritage and culture. I hope that what I learned in Fyrkat, Hobro and Randers may someday work its way into the way such preservation is done in the US.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home