Fregatten Jylland!! An example to follow...

Welcome to the mighty naval frigate Jylland!

This incredible museum ship built in 1860 is one of Denmark's first steam-powered naval vessels and a veteran of the firey Battle of Helgoland in 1864. She now stands permanently drydocked in the remote little coastal town of Ebeltoft, Denmark where crowds flock to see the ship. More significantly to people like me, Jylland is a shining example to the international maritime heritage community because of the Fregatten Jylland Museum's cutting-edge developments in the field of long-term, out-of-water, vessel preservation. The innovations seen here are unprecedented and hugely successful and should be considered if not adopted by museums around the world--especially in Seattle for the long-suffering schooner Wawona; even Vasa Museet is currently considering certain spects of the Jylland example for its long-range structural preservation plans for Vasa.

Jylland ('Jutland') has far fewer guns than Vasa, being a fast and agile little frigate rather than a heavy ship of the line, but she was still a formidable vessel. In addition to the modern cannons being produced in the 1860s, Jylland carried an even newer and more revolutionary weapon...

Jylland ('Jutland') has far fewer guns than Vasa, being a fast and agile little frigate rather than a heavy ship of the line, but she was still a formidable vessel. In addition to the modern cannons being produced in the 1860s, Jylland carried an even newer and more revolutionary weapon... ... steam propulsion! (note the funnel) Jylland carried a bulky 400 horsepower, 2-cylinder steam engine designed to be installed on its side deep in the bottom of the ship, safe from enemy shot penetrating the upper hull and leaving the gundecks open for gunnery.

... steam propulsion! (note the funnel) Jylland carried a bulky 400 horsepower, 2-cylinder steam engine designed to be installed on its side deep in the bottom of the ship, safe from enemy shot penetrating the upper hull and leaving the gundecks open for gunnery.  The hissing and wheezing engine turned a large, two-bladed, bronze propeller. The Danish Navy had decided to use the novel concept of the propeller rather than the more typical paddle wheel which would be far more vulnerable to the enemy's cannon fire. Remarkably, the navy also designed Jylland's propeller so that it could be retracted up into the hull to reduce resistance when the ship was under sail.

The hissing and wheezing engine turned a large, two-bladed, bronze propeller. The Danish Navy had decided to use the novel concept of the propeller rather than the more typical paddle wheel which would be far more vulnerable to the enemy's cannon fire. Remarkably, the navy also designed Jylland's propeller so that it could be retracted up into the hull to reduce resistance when the ship was under sail. Jylland also carried a full rig even though she was officially a primarily steam-driven ship. When not in battle or when making long voyages, sails were preferred because of the ship's limited space for stowing coal. This alternate propulsion method became particularly useful when Jylland was promoted to the status of being the personal transport vessel for the King of Denmark in 1873.

Jylland also carried a full rig even though she was officially a primarily steam-driven ship. When not in battle or when making long voyages, sails were preferred because of the ship's limited space for stowing coal. This alternate propulsion method became particularly useful when Jylland was promoted to the status of being the personal transport vessel for the King of Denmark in 1873. Jylland went into the shipyard for several months that year to have a new deckhouse built back aft with luxurious cabins (shabby by royal standards) for the King and his advisors and a number of her cannon were removed to make space for the royal dining room. Thus, after 1874, the Jylland served as a floating embassy, a vessel intended to serve King Christian IX on his diplomatic missions around Europe and the Atlantic. The most remembered of these travels were his voyages to Ireland and the Virgin Islands(1887). Upon her return from the latter trans-oceanic voyage, one that was indeed long and punishing to the old ship, Jylland was retired from active sea-duty and became a permanently moored training ship for naval cadets.

Soon she was further demoted, having her masts removed and a roof built over her decks making her into a sort of floating barracks and office building serving the new and mighty warship Sjealland. There she languished, slowly rotting.

Then in 1908 a glimmer of hope appeared for the old ship; Instead of sending the Jylland to the wreckers as was usually done with obsolete and decrepit warships, the Danish Navy decided to sell the Jylland on the public market. Thus, that year Jylland completed her government service, was stricken from the navy books, and embarked a new life in the private sector.

In the decades that followed, Jylland went through many of the same trials and tribulations endured by the venerated lumber and cod fishing schooner Wawona, now awaiting sentencing in Seattle after 109 years of stellar service.

The key was these gentlemen, born leaders and fundraisers passionate about maritime history. Ole introduced me to the fellow on the right and we spoke about the process a bit--although my total lack of Danish language skills and his mediocre grip on English caused some difficulty. These men put it together, inspiring and assembling everything needed to transform 350 tons of dry-rot into a taught and fully-rigged warship standing as the centerpiece of a wildly popular museum. Through pure grit and determination, they ended the 70 year legacy of failed attempts and progressively worsening deterioration and gave Jylland a new life.

The key was these gentlemen, born leaders and fundraisers passionate about maritime history. Ole introduced me to the fellow on the right and we spoke about the process a bit--although my total lack of Danish language skills and his mediocre grip on English caused some difficulty. These men put it together, inspiring and assembling everything needed to transform 350 tons of dry-rot into a taught and fully-rigged warship standing as the centerpiece of a wildly popular museum. Through pure grit and determination, they ended the 70 year legacy of failed attempts and progressively worsening deterioration and gave Jylland a new life. As the project gathered momentum, a site was chosen for the ship and the envisioned museum along the Ebeltoft waterfront and construction of a coffer dam began in 1983-84. The Jylland was coaxed into the structure, set on blocks, and then the final wall of the coffer dam was pounded into the clay harbor bottom. Then the work on Jylland began. Crews documented every detail of the ship, recording every dimension and curve of every timber for the upcoming restoration process.

As the project gathered momentum, a site was chosen for the ship and the envisioned museum along the Ebeltoft waterfront and construction of a coffer dam began in 1983-84. The Jylland was coaxed into the structure, set on blocks, and then the final wall of the coffer dam was pounded into the clay harbor bottom. Then the work on Jylland began. Crews documented every detail of the ship, recording every dimension and curve of every timber for the upcoming restoration process.  In 1990--6 years after Jylland entered the drydock--the last of the water was pumped out and Jylland sat on a straight keel for the first time since she was built 130 years earlier. By then the cofferdam drydock had been roofed over to protect the restoration work while the decks and virtually all the rotted planks and timbers were ripped off down to the waterline.

In 1990--6 years after Jylland entered the drydock--the last of the water was pumped out and Jylland sat on a straight keel for the first time since she was built 130 years earlier. By then the cofferdam drydock had been roofed over to protect the restoration work while the decks and virtually all the rotted planks and timbers were ripped off down to the waterline. Then the reconstruction work began. Building on the careful documentation done during the disassembly of the ship, carpenters and shipwrights shaped new ribs, set them in and replanked the hull and decks. Meanwhile the royal aft cabins were reconstructed, the masts were rebuilt (pine planking over steel pipe), and the ship's original cannons--stuck in the ground as decorative fenceposts--were dug up, sandblasted, and restored on new carriages.

Then the reconstruction work began. Building on the careful documentation done during the disassembly of the ship, carpenters and shipwrights shaped new ribs, set them in and replanked the hull and decks. Meanwhile the royal aft cabins were reconstructed, the masts were rebuilt (pine planking over steel pipe), and the ship's original cannons--stuck in the ground as decorative fenceposts--were dug up, sandblasted, and restored on new carriages. As the work proceeded, interest and funding grew and more and more specialists from the maritime sector came to work on Jylland, cutting and shaping timbers, caulking seams, reforging the ship's fittings, making spars, or working on the rigging.

As the work proceeded, interest and funding grew and more and more specialists from the maritime sector came to work on Jylland, cutting and shaping timbers, caulking seams, reforging the ship's fittings, making spars, or working on the rigging.

Ole brought his expertise as a ropemaker to the project, laying most of the rope used in the lower rig himself (the museum opted to use synthetic line in the topmasts and topgallant masts for maintenance reasons).

Ole brought his expertise as a ropemaker to the project, laying most of the rope used in the lower rig himself (the museum opted to use synthetic line in the topmasts and topgallant masts for maintenance reasons).

By the time the restoration work was officially finished in 1994, Jylland was a 60% new ship. What is remarkable is not how high this percentage is, but rather how low it is. For a wooden ship of even half her age, 70% and 80% reconstructions are not uncommon. Wood weakens and rots and therefore must be routinely replaced, piece by piece. Even working sailingships in commercial service underwent slow renewals of their almost their entire structure during their careers. C.A. Thayer (Wawona's sistership) is just completing a 85%-90% reconstruction in San Francisco and the Charles W. Morgan at Mystic Seaport is nearly 65%-70% rebuilt and is about to return to the shipyard again. The USS Constitution--America's most famous historic wooden vessel--is less than 10% original wood (Vasa's 95% original wood is in a league of its own and for technical reasons, isn't a fair comparison). Therfore, Jylland's 40% original wood--essentially everything below the waterline--is an extraordinary achievement in the field of historic vessel preservation.

The key to the preservation success of Jylland lies in an ingenious and revolutionary idea in how permanently dry-docked ships should be supported. Traditionally, museum ships preserved and exhibited out of water have been supported the same way as a ship in drydock would be for routine repairs or hull-painting--undeniably, temporary situations.

Typically, this includes little more than a row of wooden or concrete blocks evenly spaced beneath the keel and a few additional blocks or posts to keep the ship from rolling to one side or another. The method is crude, but serves its purpose and offers decent support and access to the bottom of the hull while the ship is hauled out. In more recent decades--especially with fragile ships such as Vasa, a cradle method has been used wherein the ship sits nestled in a cradle with contours more or less following those of the ship. This method is far more supportive and effective for preserving a perpetually flexing and settling wooden hull.

The problem with these two methods--the blocking method and the cradle method--is that they only support the ship from underneath. This means that the weight on the ship's timbers steadily increases the lower you go in the ship until the entire compounded weight of the vessel is pressing down on the bottom of the ship. Thus, even if the weight is distributed as evenly as possible on the blocking or the cradle, the lower portions of the ship continue to suffer under intense and ultimately destructive pressure.

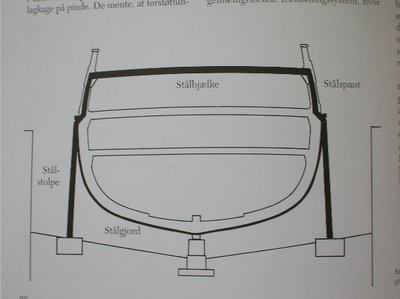

The new and modern hull support philosophy employed in the Jylland project (illustrated here) completely changed the longevity projections for a permanently drydocked ship. The crucial elements of this new philosophy are 1.) the hull is designed to be supported by water pressure, not localized blocking or cradle frames. Therefore, the support system should aim to recreate the forces of water pressure on the hull, and 2.) an aging and frail historic vessel should not be expected to carry the enormous weight of its decks.

Based on these concepts, the Fregatten Jylland Museum designed a support system that essentially transformed the ship into a free-standing building, its mass conceptually divided into several vertical sections and individually supported by new structures.

First, the decks are 'lifted' off the ship by replacing several of the rotten beams with steel girders supported by tall buttresses reaching up the outside of the ship from the bottom of the drydock (see heavy black line in diagram). This removes the weight of the decks and upper bulwarks from the lower (and in this case, original) portion of the hull.

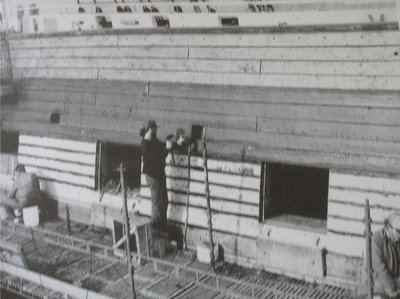

Here the steel butresses can be seen climbing to just above the ship's waterline where they go inside the hull between the ribs to join with the deck beam girders. Undeniably, they are both somewhat structurally and aesthetically invasive, however, the severe rot in the upper hull required extensive intrusion by the conservation/restoration crews anyway and the buttresses are designed to simulate the thin and elegant support timbers usually used in graving docks.

Here the steel butresses can be seen climbing to just above the ship's waterline where they go inside the hull between the ribs to join with the deck beam girders. Undeniably, they are both somewhat structurally and aesthetically invasive, however, the severe rot in the upper hull required extensive intrusion by the conservation/restoration crews anyway and the buttresses are designed to simulate the thin and elegant support timbers usually used in graving docks.  Ole and Annette walking under Jylland's big bow. Note the hull straps and keel blocking.

Ole and Annette walking under Jylland's big bow. Note the hull straps and keel blocking. Then, to recreate the forces of water pressure, the bottom of the ship--where almost all the fragile original timbers and planking are--is supported by big steel straps that run from the tops of the buttresses, down under the hull and back up to buttresses on the other side, supporting the hull in a steel sling (see diagram again). These straps squeeze the ship back together like barrel hoops, preventing her sides from springing open fore and aft under the ship's great weight and sagging in port and starboard halves.

The other mode of support for the bottom of the ship is the traditional keel blocking. This takes the load of the heavy keel as well as part of the load of the decks which is transferred to the keel by internal supports in the ship (we'll visit those later). Also, notice what an open and airey view of the hull this support method offers. Visitors can walk under the ship and fully appreciate the beautiful curves of the hull while the blocking and the buttresses--all arranged in narrow, unobtruisive rows--they almost seem to frame the hull like a grand nautical cathedral.

The other mode of support for the bottom of the ship is the traditional keel blocking. This takes the load of the heavy keel as well as part of the load of the decks which is transferred to the keel by internal supports in the ship (we'll visit those later). Also, notice what an open and airey view of the hull this support method offers. Visitors can walk under the ship and fully appreciate the beautiful curves of the hull while the blocking and the buttresses--all arranged in narrow, unobtruisive rows--they almost seem to frame the hull like a grand nautical cathedral. While we are down here we might as well have some fun poking about; we gotta go aft and take a look at the propeller. You'll have to pardon the scaffolding--the stern needs a little maintenance--but you can still see this early propeller with its two huge bronze blades.

While we are down here we might as well have some fun poking about; we gotta go aft and take a look at the propeller. You'll have to pardon the scaffolding--the stern needs a little maintenance--but you can still see this early propeller with its two huge bronze blades. Looking straight down the propeller trunk and through the bottom of the ship.

Looking straight down the propeller trunk and through the bottom of the ship.One of the amazing things about this ship is that the propeller could be disengaged from the engine and hoisted up through this trunk until it was out of the water. That way, those huge blades wouldn't slow the ship down when she is under sail. Apparently hauling the thing up was a major feat. It took a good portion of the crew slaving at the capstan to lift the 5 ton propeller assembly out of position.

(However, as impressive as this system was, the weight of the prop conributed significantly to the severe hogging of the hull).

Despite the rather primitive design (today, props are often smaller, spin much faster, made of steel, and have 4 or 5 blades with adjustable pitch--they can even be feathered to eliminate drag when not in use), Jylland's steam engine and protected propeller made her a high-tech, futuristic naval vessel in 1860.

Walking under her sharp bow you can almost see and hear the frothing bowwave she would have plowed up charging along under sail or even with that big steam engine. Reportedly, that propeller could churn up the waters until she was running at just about her 14-knot hull speed. That just goes to show how misleading a steam engine's horsepower is; it is the incredible torque that makes the real difference.

Walking under her sharp bow you can almost see and hear the frothing bowwave she would have plowed up charging along under sail or even with that big steam engine. Reportedly, that propeller could churn up the waters until she was running at just about her 14-knot hull speed. That just goes to show how misleading a steam engine's horsepower is; it is the incredible torque that makes the real difference.

She must have been a real terror when she charged into battle off Helgoland on that summer day in 1864, knifing her way through the swell with her engine clanking and hissing at full speed and her guns run out and ready to fire.

This photo also serves to emphasize more of the countless ingenious design elements of the Jylland project. Once again, note how free and clear the view of the hull is despite this far more extensive--and invasive--support system.

In front of the ship, the project designers had the vision to build a small amphitheater under the looming bow for tours, students, or music performances. As Ole knows all too well, it is also a wonderful place to just sit and admire the great ship perched in the drydock.

Because Jylland's anchor weighs almost 5 tons, placing it on the ship was not advisable--indeed, from a preservation perspective, to do so would have been outright unresponsible as such an enormous weight in such a concetrated spot would put undue stress on the hull. Therefore, the anchor was laid on the drydock bed in front of the ship while the anchors hung on the ship itself are hollow fiberglass copies.

Part of what I like about this exhibition method is that visiors are allowed under the ship to see how she is built and to note the many marks of her long years that are still visible on her green, copper hull-plating. Visitors are encouraged to come down these staircases into the cofferdam-drydock to gawk at the ship and develop further understanding of the unique technological creation before them.

Part of what I like about this exhibition method is that visiors are allowed under the ship to see how she is built and to note the many marks of her long years that are still visible on her green, copper hull-plating. Visitors are encouraged to come down these staircases into the cofferdam-drydock to gawk at the ship and develop further understanding of the unique technological creation before them.

These gangplanks bring visitors aboard at all levels from the keel to the upper deck making an onboard tour a sort of choose-your-own-adventure.

The only place you can't go is aloft--for obvious reasons. Going back to my fascination with the support system pioneered by the Fregatten Jylland Museum, the rig is also independently supported so as to reduce strain on the hull. Although the masts are still stepped on the keel and hundreds of lines composing the standing and running rigging still tether the hull and rig together, the strain put on the rig by the ewind is actually borne by several master shrouds that run down to concrete anchors buried in the bottom of the drydock.

The only place you can't go is aloft--for obvious reasons. Going back to my fascination with the support system pioneered by the Fregatten Jylland Museum, the rig is also independently supported so as to reduce strain on the hull. Although the masts are still stepped on the keel and hundreds of lines composing the standing and running rigging still tether the hull and rig together, the strain put on the rig by the ewind is actually borne by several master shrouds that run down to concrete anchors buried in the bottom of the drydock.

Just a few months ago, the Fregatten Jylland Museum completed a new museum facility alongside the ship. It is really quite tasteful and non-ostentatious (or even particularly outspoken) for a modern museum building and they are the perfect supplement to the Ebeltoft waterfront, currently highlighted by the Jylland's towering masts. There is something about the way those wood (sheathed) spars and (mostly) hempen rigging stand there high over the roof that I find to be so much nicer than Vasa Museet's imperssionist, steel, roof-top masts.

As you can see it is really a very nice understated building constructed of natural materials--with a nifty but quite possibly irrelevant little moat--that falls neatly between the monolithic marble temple-museums of olde and the modern and sterile space-age designs that are popular in the museum world today.

As you can see it is really a very nice understated building constructed of natural materials--with a nifty but quite possibly irrelevant little moat--that falls neatly between the monolithic marble temple-museums of olde and the modern and sterile space-age designs that are popular in the museum world today.

Passing through from the parking lot to the seaside of the museum buildings, you can really see the pleasant nature of these facilities. With their simple design and timber and glass construction they have both an 18th century industrial feel as well as a modern, eco-friendly one. They remind me of some of the tasteful modern wood constructions around Seattle like Bill Gates' house, Camp Norwester's dining hall in the San Juans, or Islandwood Environmental Learning Center on Bainbridge Island. It works...

Inside, the buildings are wonderfully airey and bright with light-colored, unfinished wood. This is the museum's very stylish cafeteria looking out at the Jylland and the harbor beyond. It is well designed, pleasing, and functional--worth noting for those of you considering such museum issues.

Inside, the buildings are wonderfully airey and bright with light-colored, unfinished wood. This is the museum's very stylish cafeteria looking out at the Jylland and the harbor beyond. It is well designed, pleasing, and functional--worth noting for those of you considering such museum issues.

The exhibit halls themselves are housed in the same structure. However, as these buildings were just opened in the last year, there is still considerable need for exhibit development. Currently, most of the exhibit hall is serving as an art gallery for paintings and photographs of Jylland. There is no accompanying interpretation or storyline, it is simply a gallery. There are a few educational displays set up and a rather nice informational film, yet it remains clear that the potential of these new buildings is just beginning to be explored.

In one of the other buildings on the site stands the old rigging loft, a place where Ole was drawn to like a dog to a bad smell. Infact, the place reeked of fresh tar, but to guys like us, that is the smell of dreams... suddenly I have an entirely new understanding of how the canine mind works. The walls were hung with an assortment of spare blocks, wrapped lines, and coils of this and that, and a short ropewalk had been set up across the floor.

In one of the other buildings on the site stands the old rigging loft, a place where Ole was drawn to like a dog to a bad smell. Infact, the place reeked of fresh tar, but to guys like us, that is the smell of dreams... suddenly I have an entirely new understanding of how the canine mind works. The walls were hung with an assortment of spare blocks, wrapped lines, and coils of this and that, and a short ropewalk had been set up across the floor. Oustide, the Fregatten Jylland Museum's designers had had the vision to build a guest dock for summer yachtsmen. I remembered that Mystic Seaport had done this too, creating an excellent source of revenue for the museum and providing enthusiastic boaters an extra-special opportunity.

Oustide, the Fregatten Jylland Museum's designers had had the vision to build a guest dock for summer yachtsmen. I remembered that Mystic Seaport had done this too, creating an excellent source of revenue for the museum and providing enthusiastic boaters an extra-special opportunity.

Like Mystic Seaport, visitors would have the run of the museum, wandering through the exhibit halls/art galleries....

... the gift shop, the restaurant, the Jylland model room, the ship...

... the gift shop, the restaurant, the Jylland model room, the ship...

...and the historic ship's wharf that is also part of the museum. The Fregatten Jylland Museum, ever aware of the potential of the future, has been expanding its operations in the museum buildings ashore and the new wharf out front, acquiring a number of vessels of some importance in the story of the region's maritime heritage.

Among them there is a lovely German schooner like those that plied the Southern Baltic and Eastern Denmark for generations...

Among them there is a lovely German schooner like those that plied the Southern Baltic and Eastern Denmark for generations...

...displaying some of the characteristic design features of her background, like this unusual, long, overhanging German stern.

The Museum has also acquired one of the last remining wooden lightships in the region.

The Museum has also acquired one of the last remining wooden lightships in the region. The old floating lighthouse is in bad shape, but she has only just recently arrived and her future is now unquestionably bright.

The old floating lighthouse is in bad shape, but she has only just recently arrived and her future is now unquestionably bright.

No maritime museum is complete without an example of the most common point of human contact with the seas, the fishing boat. Painted a traditional Danish fishingboat blue, this recently-acquired little craft also awaits restoration.

...as does this peculiar little rescue boat designed to plow through the violent surf to get out to a stranded vessel, a common occurance on the stormy, island-strewn Danish coasts.

The Fregatten Jylland Museum even got hold of one of these, a fishing boat outfitted for coastal patrol and defense. I was particularly excited to see this as it is a Danish example of the very same phenomenon of civilian vessels at war that is the subject of my book.

Last, the tip of the little breakwater and pier that has been built out around the little artificial harbor offers one of those clichéd but treasured maritime museum attributes, a signal mast and cannon fortification.

But there remains one more brilliant aspect of the Fregatten Jylland Museum, the shipyard.

Few maritime museums in the world today feature a working shipyard to maintain their floating collections. Most send their craft off to commercial yards for maintenance. Mystic Seaport has long been proud of being the only shipyard in the world with its own working shipyard. That single facility--made possible by a steady supply of work from their huge floating collection and a big operating budget--has saved the museum untold fortunes in maintenance and preservation costs. However, the Mystic Seaport innovation may be about to be eclipsed. The Fregatten Jylland Museum, now a second maritime museum with its own shipyard, has opened and is restoring vessels. However, the Jylland project has brought a new twist to the museum shipyard concept.

Wooden yacht hauled out for caulking.

Wooden yacht hauled out for caulking.The Jylland's shipyard is not a true part of the museum. It stands on the museum grounds in a museum-owned building and it works on the museum's vessels, however the shipyard is--at least on paper--its own, independent business.

Annette and Ole talking with one of the shipwrights (under the hull)

Annette and Ole talking with one of the shipwrights (under the hull)Here's how it works: A shipwright leases the space in a contract that allows him to run his own, independent shipyard business in a high-quality facility on the museum grounds at a very low rate. Just like any commercial yard, the shipwright is free to perform work on any vessels he chooses regardless of ownership. The only catches are that the yard must give priority to the museum ships and the shipyard employees must be willing to have museum visitors watching them at work.

Freshly caulked and tarred seams on a yacht getting a spring refit at the Jylland yard.

What this quasi-joint arrangement achieves is job security for the shipyard workers and as a result, cost security for the museum. By being able to bring in work from outside the museum, the shipyard can keep enough work coming in the door to keep the carpenters and shipwrights on the payroll. A museum cannot necessarily do that given its countless other financial responsibilities--often keeping a full-time shipyard crew is just not feasible. Thus, when the museum can pay to have these crews work on museum vessels, they do, otherwise, the shipwright is free to find customers elsewhere.

The yacht hauled out in the Jylland yard in front of the Jylland herself.

The yacht hauled out in the Jylland yard in front of the Jylland herself.

By providing a low-cost site and allowing the shipwright to find other customers to stay in business, the museum guarantees itself a professional, on-site shipyard to carry out its maintenance and restoration work for unbelieveably low rates. It is a good move for all involved.

In addition to the marine railway, the Jylland shipyard is also equipt with a brand new indoor work facility meeting all the latest standards for labor and environmental conditions. This photo shows the spirit of the contract very clearly; in the foreground you have the Jylland's mizzen mast down for repairs while in the back of the room there is a modern fiberglass sailboat in for a little interior cabinetry work. While we're here, I ought to point out another innovative aspect of the Fregatten Jylland Museum; the structural frames of all the museum faicilities (restaurant, exhibit hall, gift shop, and shipyard) are all of historical significance themselves. Until just two years ago, these frames stood on a Danish naval base as the two-hundred year-old support for the Danish Navy's old dockyards. When the buildings were to be torn down, the museum petitioned for the timber for its historical value and actually had all of it donated to the project.

While we're here, I ought to point out another innovative aspect of the Fregatten Jylland Museum; the structural frames of all the museum faicilities (restaurant, exhibit hall, gift shop, and shipyard) are all of historical significance themselves. Until just two years ago, these frames stood on a Danish naval base as the two-hundred year-old support for the Danish Navy's old dockyards. When the buildings were to be torn down, the museum petitioned for the timber for its historical value and actually had all of it donated to the project.

The shipyard also has extensive outdoor facilities including this big boatshed where additional ship's boats for Jylland are bing built...

...where the shipyard's own sawmill is located... ...and its accompanying stock of rare oaks, sliced into the dimensions of Jylland's enormous planks.

...and its accompanying stock of rare oaks, sliced into the dimensions of Jylland's enormous planks. ...and all of this is right on the museum grounds, right beside the Jylland herself as if she were docked in the Danish Navy Dockyards awaiting a few repairs before steaming off to war again.

...and all of this is right on the museum grounds, right beside the Jylland herself as if she were docked in the Danish Navy Dockyards awaiting a few repairs before steaming off to war again. And clearly, no job is too large for the chaps working in this yard. From skiffs to frigates, they do it all...

And clearly, no job is too large for the chaps working in this yard. From skiffs to frigates, they do it all... When Ole, Annette, and I visited, they were working on Jylland's mizzen mast which had begun to rot and had to be taken down (the rotten top actually snapped off when the mast was lowered onto the quay by a crane--just like Wawona...)

When Ole, Annette, and I visited, they were working on Jylland's mizzen mast which had begun to rot and had to be taken down (the rotten top actually snapped off when the mast was lowered onto the quay by a crane--just like Wawona...)

Okay, who is ready to go aboard?!!

We'll start by coming around to the port side gangplanks--and we're already seeing some very impressed-looking visitors come up from the bottom of the drydock, the end of the typical tour route. Oooo, it'll be good!

Just gazing up at the rigging as you approach, watching the perspective on each spar and line changing as you walk by, almost as if the great ship were steaming past...she's clearly a grand vessel of a most distinguished stature. What an achievement for this museum.... ...and even though her mizzen mast is missing (it is the pre-tourist season. Now is the time to do it), she is still a proud ship with a menacing double-row of cannon ready to fight for Denmark.

...and even though her mizzen mast is missing (it is the pre-tourist season. Now is the time to do it), she is still a proud ship with a menacing double-row of cannon ready to fight for Denmark. The Danish colors proudly wave in the stiff sea breeze...

The Danish colors proudly wave in the stiff sea breeze... ..and before you know it, we're standing on the quarterdeck looking out over the great ship cluttered with lines, spars, and guns, each one having a unique and important role in operating the ship.

..and before you know it, we're standing on the quarterdeck looking out over the great ship cluttered with lines, spars, and guns, each one having a unique and important role in operating the ship.

The cannons sit alertly at their ports, aiming out over the low roof of the museum at the hamlet of Ebeltoft and the canvas hatchway covers flop heavily in the wind. Hidden below the shot-stopping bulwarks, the ship's gloss-varnished double wheel glitters in the sun...

Hidden below the shot-stopping bulwarks, the ship's gloss-varnished double wheel glitters in the sun... ...and you can almost feel the ship rolling at sea as you take hold of the handrails and descend to the maindeck.

...and you can almost feel the ship rolling at sea as you take hold of the handrails and descend to the maindeck. As you stand there, trying to imagine the carnage on that day in 1864 off Hegolund, Ole casually points out the condition of the heavy ropes he made for securing the cannon a few years ago. The weather has gotten to them and he thinks he will have to replace them soon...

As you stand there, trying to imagine the carnage on that day in 1864 off Hegolund, Ole casually points out the condition of the heavy ropes he made for securing the cannon a few years ago. The weather has gotten to them and he thinks he will have to replace them soon...

Given the peaceful atmosphere of traveling with these two, perhaps it is easier to look aft at the royal cabins and imagine the King coming out for a stroll on the deck before lunch.

Moving forward to the big funnel between the fore and main masts, one can try to perceive the stink of burning coal or the black greasy soot that must have smothered the lower masts. Taking a closer look at the funnel, one can see the joints betwen the sections of this retractable, telescoping smokestack. Remarkable design... ...my, that engine must have made a messy stink onboard....

...my, that engine must have made a messy stink onboard.... At the foot of the foremast we find a rather intriguing innovation on this museum ship; an elevator. There is no question that a historic ship is about the worst kind of museum imaginable for the disabled--so many steep steps, sharp curves, tripping obstacles etc. Yet, the Fregatten Jylland Museum crew was undaunted and removed a series of hatch gratings to permit the inclusion of this modern device. There is no question that it is a new addition, and thus, despite its inherent ugliness, it does not seem to interfere with the presentation of the ship as a whole.

At the foot of the foremast we find a rather intriguing innovation on this museum ship; an elevator. There is no question that a historic ship is about the worst kind of museum imaginable for the disabled--so many steep steps, sharp curves, tripping obstacles etc. Yet, the Fregatten Jylland Museum crew was undaunted and removed a series of hatch gratings to permit the inclusion of this modern device. There is no question that it is a new addition, and thus, despite its inherent ugliness, it does not seem to interfere with the presentation of the ship as a whole.

Well, we'd better test this museum innovation and go below. Ever seen an elevator with a button labelled "gundeck?"

Well, here we are, on the Jylland's gundeck--also home to much of her crew. Tables and hammocks were usually added to the clutter of cannons, ringbolts, and chains.

Well, here we are, on the Jylland's gundeck--also home to much of her crew. Tables and hammocks were usually added to the clutter of cannons, ringbolts, and chains.

In the forward part of the gundeck stands the crew's galley (captain and king had their own). The museum decided that although there would be little to no text labels onboard the ship--they wanted her to appear as she should and speak for herself, so get a brochure at the admissions desk and read it if you wanna know more--they would put in a few mannikan scenes to illustrate the function of certain parts of the ship.

Here we pass one of the ship's heavy, solid capstans while a plastic gun crew loads a cannon in the background.

Here we pass one of the ship's heavy, solid capstans while a plastic gun crew loads a cannon in the background. Moving aft we eventually pass into "Officers' country." This was the officers' dining table. Note the steering lines overhead running from the wheel to the rudderhead.

Moving aft we eventually pass into "Officers' country." This was the officers' dining table. Note the steering lines overhead running from the wheel to the rudderhead.

Their dining room might be slightly different from yours at home in that it includes four big cannons that--despite their lovely woodwork--are far from strictly decorative.

Continuing aft we reach the King's salon in the far stern of the ship. For being the official sitting room of the King and his entourage at sea, it was remarkably sparse. Then again, with such an impressive ship, who wants to sit in an ordinary living room down below?

Dropping down a deck through a hatch, we come to the former officer's quarters. They all had their own rooms--now only marked by painted lines along the deck where thin walls once stood. This space, directly below the King's quarters, was so frequently modified over the years and so thoroughly decayed by the time of the restoration, that the museum leadership decided to leave the space open and exhibit the unique hull forms of this area instead.

Moving forward we pass through the orlopp deck where much of Jylland's crew slept and ate. It lies just below the waterline and thus was poorly ventilated and lit only by a few dim lanterns. Today, the space is used for special events and can be rented out to anyone wishing to use the venue. The museum's restaurant has become well-versed in negotiating the countless obstacles to catering events onboard a ship.

Going aft again, we drop down from the orlopp deck to the hold where we can finally marvel at the ship's original timbers and the unique X-pattern hull construction used at the end of the wooden warship era.

Going aft again, we drop down from the orlopp deck to the hold where we can finally marvel at the ship's original timbers and the unique X-pattern hull construction used at the end of the wooden warship era.  We can also finally see the internal elements of the innovative Fregatten Jylland Museum's structural support system; numerous rows of steel pipes supporting the upperdecks from the keelson, transferring the load from the overburdened ribs to the more capable keel.

We can also finally see the internal elements of the innovative Fregatten Jylland Museum's structural support system; numerous rows of steel pipes supporting the upperdecks from the keelson, transferring the load from the overburdened ribs to the more capable keel. The museum has created visitor access to the hold by installing a boardwalk down the starboard side, allowing one to walk through the cavern and see the last remains of the original 145 year-old frigate Jylland...

The museum has created visitor access to the hold by installing a boardwalk down the starboard side, allowing one to walk through the cavern and see the last remains of the original 145 year-old frigate Jylland... ...and their modern solution to the ever-present fact that wooden hulls are always settling.

...and their modern solution to the ever-present fact that wooden hulls are always settling.

Part of what enables us to enjoy the eleoquent curves of the hull is the fact that Jylland's big steam engine went to the melting pot many decades ago, lost during the ship's long years of uncertain fate. The museum has plans to build a replica to display ashore, but for now, only the worn and rutted, oil-stained wooden foundation amidships attests to its former presence. Looking forward at the sweep of the hull closing in to meet in the sharp prow, it is possible to see what a highly engineered science ship construction had become by the end of the wooden ship era and the stylistic direction it would take in the coming days of steel and iron girders.

Looking forward at the sweep of the hull closing in to meet in the sharp prow, it is possible to see what a highly engineered science ship construction had become by the end of the wooden ship era and the stylistic direction it would take in the coming days of steel and iron girders. Returning amidships, we can step out through what was intended as an emergencey exit, but has since become a standard part of one's tour through the ship. Being able to pass directly from the hold to the outside of the ship offers a rare conceptual link between the interior and exterior of a wooden ship that clearly serves to excite many visitors.

Returning amidships, we can step out through what was intended as an emergencey exit, but has since become a standard part of one's tour through the ship. Being able to pass directly from the hold to the outside of the ship offers a rare conceptual link between the interior and exterior of a wooden ship that clearly serves to excite many visitors. ...and then, to step forward and look up at the great hull, the menacing cannons, and the towering rig above is an emotional sight that cannot be captured here...

...and then, to step forward and look up at the great hull, the menacing cannons, and the towering rig above is an emotional sight that cannot be captured here... With that, we circle about the bottom of the drydock, inspecting the big bronze propeller, the anchor, and the daunting bow before climbing the stairs to the quayside again.

With that, we circle about the bottom of the drydock, inspecting the big bronze propeller, the anchor, and the daunting bow before climbing the stairs to the quayside again.

Passing by her transom, we see the newly painted sculptures through the worker's scaffolding and the ship's name in proud, bold lettering. With that, we have seen the mighty Jylland and a few of the ground-breaking innovations of the Fregatten Jylland Museum project, an example to follow.

With that, we have seen the mighty Jylland and a few of the ground-breaking innovations of the Fregatten Jylland Museum project, an example to follow.

1 Comments:

qzz0612

canada goose outlet

ferragamo outlet

fitflops sale

merrell shoes

canada goose jackets

michael kors outlet

futbol baratas

salomon shoes

fitflops sale clearance

jordan shoes

Post a Comment

<< Home